Roots

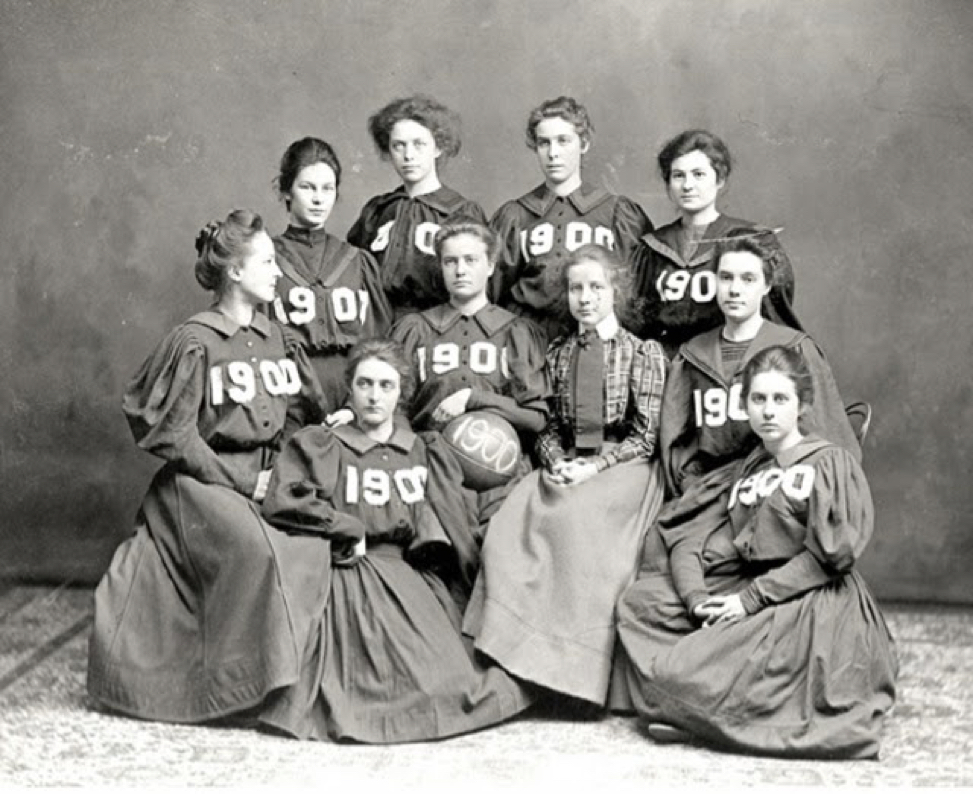

The women’s club movement was formed in the 19th and early 20th century by pioneering women who provided each other with encouraging community at a time when they needed it most. There were over 600 such groups in New York City by the 1930’s and over 5,000 nationwide.

In 1868, Fanny Fern was turned away from an all-male New York Press Club dinner honoring Charles Dickens. Fern, a popular American newspaper columnist, explained that she was invited to “listen to the speeches ‘through the crack of a door.’

One year later, Fern cofounded America’s first professional women’s club, Sorosis.

Initially, the club woman’s desire for self-improvement was viewed with resistance and disdain. “[T]he best and safest club for a woman to patronize is her home,” President Grover Cleveland wrote in the pages of the Ladies Home Journal. At that time, a club woman was unlikely to have completed professional training or higher education and she was expected to find fulfillment through motherhood. Change for many was gradual, but nothing would be the same.

By 1906, there were over 5,000 women’s clubs in existence, many of which added reform work to other edifying activities. As Eleanor Roosevelt observed in a 1922 speech, “Women are by nature progressives.” The catalog of social issues that concerned them were substantial: abuse of immigrants, substandard housing, poor sanitation, inadequate employment and educational opportunities. Black club women expanded efforts by bridging the class barrier and focusing on issues of importance to low-income women, working mothers, and tenant farm wives: education, self-improvement, and advancement.

By the 1920s, the social club wasn’t just for middle class or wealthy women. Working women met in groups under names like the Lady Flashers, the Lady Millionaires, and the Lady Liberties. In the 1970s, women’s clubs took on issues more pertinent to the times. The Jane Club of the Chicago Women’s Liberation Union maintained a network of abortion providers, and the Boston Women’s Health Collective published Our Bodies, Ourselves.

When the club movement began, women sought education and to cultivate identities outside of the home, but as times changed, so, too, did the priorities of club women. When communities needed libraries, they established them (75-80% of the libraries across the nation). When social welfare support was lacking, they provided it. When women demanded greater control over their bodies, they fought for it. Each new generation of women have found power in community, and together their determination has made the world they live in a better, more inclusive place. Today, we continue to defend our hard-earned rights, and in the tradition of club women before us, never give up pushing for more.

Alexis Coe is a women’s historian and author of Alice+Freda Forever: A Murder in Memphis.